Race, Representation, and Rotoscoping: Dee Hibbert-Jones and Nomi Talisman on ‘Last Day of Freedom’

The animated documentary short Last Day of Freedom, directed by Dee Hibbert-Jones and Nomi Talisman, tells the story of Bill Babbitt, a man who realizes that his younger brother Manny, a Vietnam vet, has committed a serious crime. Bill grapples with whether or not to turn Manny in; his decision to go to the police ultimately results in Manny’s conviction and execution by the state of California, and Bill is left reeling from the loss of his brother and his role in the outcome.

The 32-minute film, composed of starkly powerful testimony and more than 30,000 drawings by the filmmakers, had its world premiere at the Full Frame Documentary Film Festival in April, where it won the Center for Documentary Studies Filmmaker Award and the Full Frame Jury Award for Best Short. Since then, Last Day of Freedom has screened at festivals around the world, made the Oscar shortlist for Documentary Short Subject, and received an IDA Documentary Award nomination.

Hibbert-Jones and Talisman return to Durham this month to screen the film as part of Documentary 2015: Origins & Inventions, the Center for Documentary Studies’ 25th Anniversary celebration and national forum. They recently spoke with Full Frame about their animation process and entry into the documentary world.

The film touches on so many significant themes — veterans care, PTSD, racism, flaws within the criminal justice system — and Bill Babbitt’s story is so emblematic of all these issues. What was your connection to the subject matter, and how did you find Bill?

Dee Hibbert-Jones: Nomi and I have been collaborating since 2004. We’ve always been really interested in examining how individuals are impacted by larger social and political systems, and producing art projects around those stories.

Nomi Talisman: And then I got a day job in media services with a little nonprofit in San Francisco that does death penalty plea work. The organization does a lot of mitigating work with the family and friends of people on death row, and I was conducting interviews with these people. I’d often come back home after interviews and talk to Dee about how this is an angle that nobody knows anything about, how looking at the far-reaching effects of the death penalty on individuals and communities really opens up the conversation about criminal justice.

So we decided we wanted to do a project on this subject, and we asked the organization if they could give us recommendations for people to talk to. We started interviewing several people, and they all had powerful anecdotes to share, but we really wanted to find someone who was a great storyteller. So we went back to the organization, and they said, “Well, if that’s what you’re looking for, then you need to talk to Bill Babbitt.”

DHJ: So we went to talk to Bill. And immediately we realized that he was an amazing storyteller, and that his story has so many incredible angles to it; it highlights all these failures in the system and points out a lot of the issues that we’d been interested in for a long time. When we began the project four years ago, we thought that perhaps we would make some sort of installation that played with hesitations and stutterings and silences, but then we realized that Bill’s story needed telling in full, so we started on a linear narrative. We didn’t initially set out to make a film.

Can you walk us through your choice to have the piece simply be Bill’s testimony, to immerse the viewer in his experience without bringing in other perspectives? It’s not until a few title cards at the end of the film that you zoom out to talk about the larger issues and injustices of Manny’s case.

NT: We’ve had several people say to us, after seeing the film, “It’s so rare to hear somebody just talk to you for thirty minutes uninterrupted.” And I think without even thinking about it, when we started editing, we knew that Bill’s story was so powerful that we wanted people just to be carried by it. Bill does talk about Manny’s crime, and he does talk about the lawyers to some degree, but we felt that some of the details of the case muddied the narrative and interrupted the flow of Bill’s story. But the first few times we showed the film, we didn’t have the title cards at the end, and people immediately asked all these questions: “What happened in the trial? What kind of defense did Manny give? What crime did he actually commit?” So we realized we had to include those details in some way, but still allow the viewer to be carried by the story and stay with the emotional tenor of Bill’s experience and decision.

DHJ: We really talked about the notion of allowing the viewer to walk in someone else’s shoes, someone who didn’t commit any crime but is cast into an incredibly challenging position, someone who could make viewers go, “That could be me. What would I do in that situation? How would I respond?” So that was the reason we wanted to take ourselves out and remove any extraneous perspectives. The facts at the very end cap the story and provide answers to some of the questions unaddressed by Bill’s narrative. But it was very conscious to try to make everything from his point of view, in the hopes that audiences would really begin to empathize with Bill, to understand the complexity of his situation and the difficulties he’s facing.

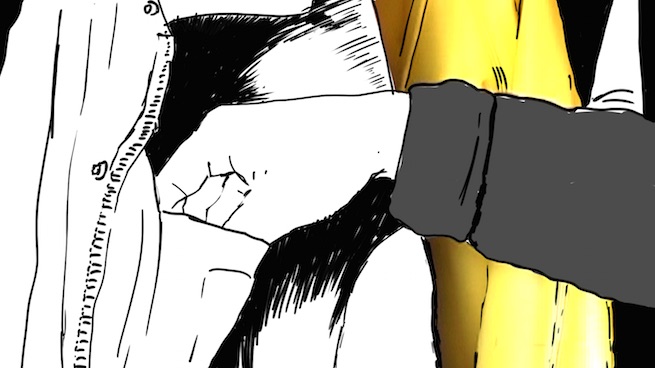

You employ all sorts of visual styles and animation techniques in the film, but the line drawings used to represent Bill as he tells his story are particularly striking. There’s a vulnerability to the spareness and shakiness of those drawings that I think allows Bill’s emotion and the stakes involved in what he’s going through to be rendered even more viscerally for the viewer. There’s also the fact that, because you’re just using simple black lines on a white background, you’re able to steer clear of the racial marker of skin color. How did you make those kinds of choices about visual representation throughout the animation process?

DHJ: You know, the one thing about animation is that nothing is an accident. You’re basically making decisions all the way along about how you want to render and represent something. We thought really hard about how we wanted Bill to be represented, and we played with a lot of different options and metaphors. Bill is holding it together, and he’s amazingly strong, but he’s also so fragile and delicate, and we wanted to represent that in the linear quality of the animation. And then we thought that by bringing in these really intimate close-ups, we could approximate the feeling of intimacy that you get with a family member.

It was also a very conscious decision on our behalf to make a line drawing out of someone who’s come across such racism in his life. Our hope was that the viewer would be forced to consider race in a new way; obviously, you still see Bill’s facial features, but the black-and-white style allows for a different way of understanding and seeing racial implication. It was a challenging visual choice to make, as we’re not part of the racial minority group that we’re representing, but Bill seems really happy with the final product.

What about the other visual styles in the film — the splashes of color, the charcoal drawings, the animation of archival footage? I’m fascinated by the conversations that must go on behind the creation of 32,000 individual drawings.

DHJ: Well, we started by breaking the film into specific time periods and scenes, and then we worked through the aesthetic treatment of each of those. We really tried to think about the emotional states at play. For example, at some points, you’re almost experiencing Manny’s post-traumatic stress disorder, and at other points you’re experiencing Bill’s heightened emotional state. We wanted to replicate with our color palette and the quality of lines that feeling of how, when something terrible happens, everything you see around you becomes really bright, and things fall away, and what’s left seems excessive and saturated and overwhelming.

NT: And we wanted different parts of the film to feel distinctive. We wanted to represent the archival footage from Vietnam differently, for example, and we played with textures and graininess to mimic the look of actual 16mm footage from army films. And then, at the beginning of the film, we used a softer color palette for the more idyllic scenes of Bill and Manny playing as kids on the beach, kind of like within a faded childhood memory. We were constantly thinking, “Does this represent a certain reality, does this represent a certain emotional space, does this represent a certain mindset?”

Have you found there to be any tension in the marriage of animation and documentary? Animated documentaries have emerged as a genre in their own right, of course, and I think that audiences and makers are thinking in increasingly expansive ways about the nonfiction form. But I’m curious if you’ve encountered any pushback from people who don’t think “documentary” is the most appropriate term to describe your film.

NT: I think the term “documentary” is absolutely appropriate. This is somebody’s story, and the facts are all there, and it represents Bill’s authentic emotional journey. But we have had people come up to us and say, “Hey, you should make a ‘real documentary’ out of this because it’s a really important story.” And it’s like, “This is a real documentary.”

DHJ: I was at a festival recently and heard a very interesting dialogue around the fact that animation is a tool, and documentary is a genre. Animation is just one tool that documentary filmmakers can employ to tell stories. And really the line should be between fiction and nonfiction; what we do as filmmakers is choose methodologies for communicating stories that fall somewhere along that line. We felt like we were able to tell this story in the most layered way through the use of animation, and that’s why we made that conceptual decision — just as we made the film the length it is because that felt like the length it needed to be.

Animation is a very time-intensive process. There is a lot of physical labor in it. We could have represented the story in a lot of different ways. We could have used other animation styles or techniques which would have sped up the process. But we really wanted to honor the story by rendering it through this particular, deliberate approach. And part of our intention with the use of animation was to open up Bill’s story to new audiences, people who might otherwise find it unbearable to watch a grown man cry on screen.

The two of you come from the art world. This is your first documentary film — which makes the success you’ve had so far all the more incredible. What has it been like working in this new mode and traveling with the film to festivals?

NT: Well, we’ve learned that the babysitters get expensive. [laughs]

DHJ: One thing I’ve been struck by is the community in the documentary world. It’s been extraordinary sitting and watching other people’s films and feeling a part of something. You don’t get that with fine art exhibitions. In a fine art context you’re often working alone.

NT: I think that in the documentary community, people are truly invested in learning something about the world. You see filmmakers and audiences all trying to learn about an issue, about people, about a particular place. I also think that because film is a time-based medium, the amount of time and attention people spend engaging with work is different than in a gallery setting, where people often just breeze through an exhibition. If you watch a film, it’s a different commitment, and I find something really refreshing about that. It’s been hugely moving to see an audience connect with the work at screenings, and it’s been hugely rewarding to get to talk about it with them afterwards.

DHJ: It’s also been really heartening to feel that a lot of the things we were trying to do with the project have actually come through. When the juries at Full Frame presented us with awards and read statements about the film, it was the first time we’d actually heard anyone articulate the representation of race and the choices in storytelling that we’d actively, consciously worked on for years. So I think we’ve been incredibly lucky that after so much time and struggle and fundraising, it feels like what we were trying to achieve with the project has been realized. We’re also kind of nervous — oh my God, what’s the next thing that we’re going to do?!